Introduction to Dynamic Capabilities

In my last post, I looked at Sarasvathy’s theory of effectuation, as an example of entrepreneurial theory which seems to match well with the lived experience of entrepreneurs, or at least the creative industry entrepreneurs I’ve been researching. I’m grateful to a former colleague, Ken Long, for introducing me to another concept that similarly bridges theory and practice, that of “dynamic capabilities”.

Pioneered by David Teece of the University of California, Berkeley, dynamic capabilities refers to a set of skills that are necessary for achieving and maintaining competitive advantage in a business. The “dynamic” part refers to the ever-changing operating environment in which a business operates and the “capabilities” part refers to management’s ability to respond to those changes in circumstances.

Dynamic capabilities refer to the particular (nonimitability) capacity business enterprises possess to shape, reshape, configure, and reconfigure assets so as to respond to changing technologies and markets and escape the zero-profit condition. Dynamic capabilities relate to the enterprise’s ability to sense, seize, and adapt in order to generate and exploit internal and external enterprise-specific competences, and to address the enterprise’s changing environment. (Teece 2009)

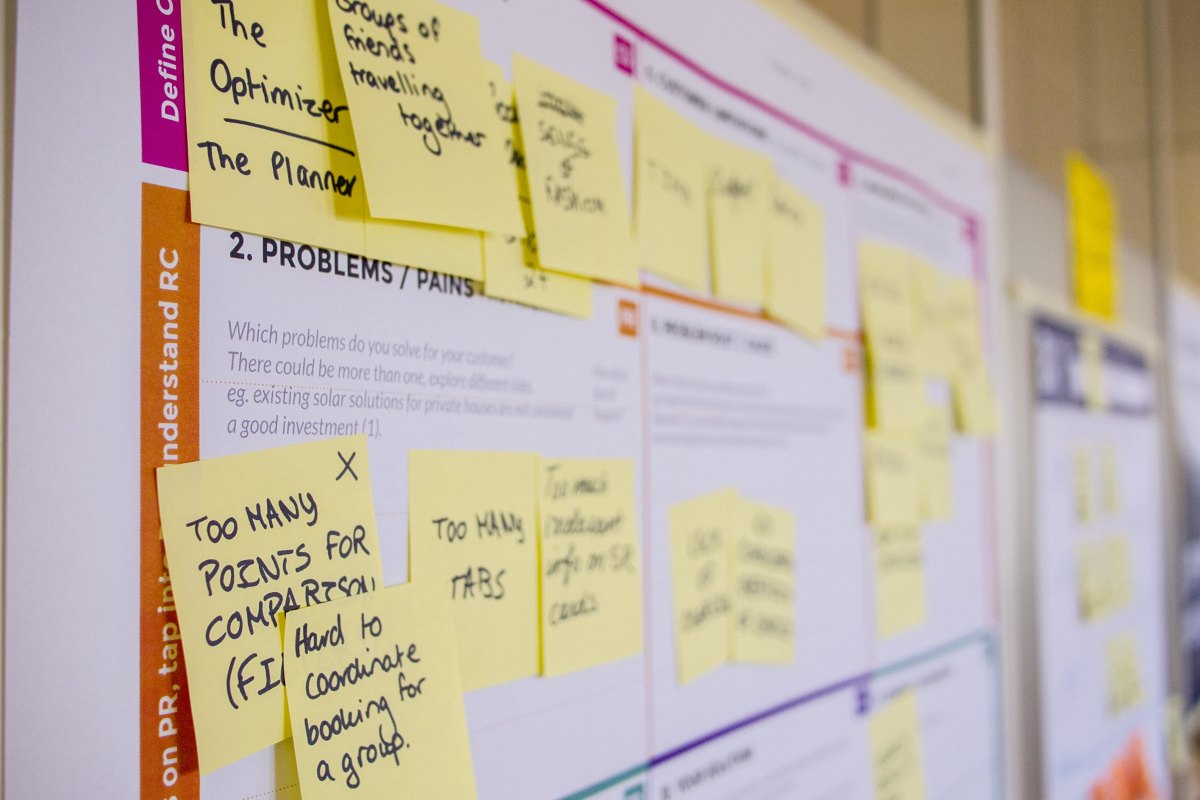

“Sense”, “seize” and “transform” are handy headings for the different types of capabilities Teece and his colleagues note. (See the diagram above for a breakdown of these categories.) (Teece 2007, p1342)

It is possible to disaggregate dynamic capabilities in three classes: the capability to sense opportunities, the capacity to seize opportunities, and the capacity to manage threats through the combination, recombination, and re-configuring of assets inside and outside of the firm’s boundaries. (Teece 2009, p205)

“Sensing” (or spotting or identifying, so many verbs) opportunities is a foundational activity of entrepreneurship. How it happens, and who undertakes it, is a recurring question within entrepreneurship research and on this blog. I like Teece’s description of it as “a scanning, creation, learning, and interpretive activity”. (Teece 2007, p1322) None of those skills – scanning, creating, learning, and interpreting – are unique to entrepreneurs. But entrepreneurs seem to have a predilection for applying those skills regularly – perhaps continually – to find (there’s another one) opportunities.

When Teece refers to “seizing” opportunities, he references another range of activities that helps exploit those opportunities, from selecting and deploying technologies to formulating business models and committing financial resources. This diverse range of tasks might sit more comfortably under the term “executing” or “activating” an opportunity, but “seizing” is fine with me, among all these competing verbs.

“Transform” is another tricky term, here being used to cluster the dynamic capabilities of managing threats to the business and reconfiguring assets to capitalise on new opportunities.

A key to sustained profitable growth is the ability to recombine and to reconfigure assets and organizational structures as the enterprise grows, and as markets and technologies change, as they surely will. Reconfiguration is needed to maintain evolutionary fitness and, if necessary, to try and escape from unfavorable path dependencies. (Teece 2007, p1335)

In my research with creative industry entrepreneurs, I see various examples of sensing, seizing, and adapting as responses to changing circumstances. As such, Teece’s work, like Sarasvathy’s, has a practical appeal to it; it seems to align well with narrative accounts of entrepreneurship.

Before I choose some examples from my research to highlight, there are a couple of other useful nuances to note. Capabilities can be categorised as exhibiting technical fitness or evolutionary fitness.

Technical fitness is defined by how effectively a capability performs its function, regardless of how well the capability enables a firm to make a living. Evolutionary or external fitness refers to how well the capability enables a firm to make a living… Dynamic capabilities assist in achieving evolutionary fitness, in part by helping to shape the environment. (Teece 2007, p1321, my emphasis).

Examples of capabilities enhancing technical fitness include management tactics such as implementing best practice or engaging in ad hoc decision-making, neither of which, according to Teece, serve to enhance a business’s competitive advantage, although both may assist improve internal performance. Not every management decision, therefore, exercises the entrepreneur’s dynamic capabilities.

It is the overlap between entrepreneurship and management that Teece is specifically interested in. For him, entrepreneurship does not stop once an opportunity has been sensed and seized; it continues to influence a business throughout its life cycle.

We have come to associate the entrepreneur with the individual who starts a new business providing a new or improved product or service. Such action is clearly entrepreneurial, but the entrepreneurial management function embedded in dynamic capabilities is not confined to startup activities and to individual actors. It is a new hybrid: entrepreneurial managerial capitalism. It involves recognizing problems and trends, directing (and redirecting) resources, and reshaping organizational structures and systems so that they create and address technological opportunities while staying in alignment with customer needs. The implicit thesis advanced here is that in both large and small enterprises entrepreneurial managerial capitalism must reign supreme for enterprises to sustain financial success. (Teece 2007), p1347)

“Entrepreneurial managerial capitalism” is a bit of a mouthful, but it does express something apt about the day-to-day operations of a business – it’s about managing a profit-seeking endeavour, with an ongoing entrepreneurial perspective. This is slightly jarring for the cultural and creative industries. As I’ve noted before, these industries encompass both profit and not-for-profit organisations, and profit-making is only sometimes present as a motivator for entrepreneurs. For the purposes of examining creative entrepreneurship, we might quietly dispense with “capitalism”, so as to examine how “entrepreneurial management” reveals itself in the narrative accounts of those who found creative industry enterprises.

Dynamic Capabilities in narrative accounts of CCI entrepreneurship

In a chapter for the forthcoming book Creative (and Cultural) Industry Entrepreneurship in the 21st Century, I use examples from the collective narratives of entrepreneurs in the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) to illustrate how models explaining how and why people start enterprises only partially fit creative industry entrepreneurs. Sensing opportunities is one of the aspects of the entrepreneurial process in which CCI entrepreneurs tend to differ from our traditional understanding. Entrepreneurial opportunities are sometimes positioned as pre-existing, hitherto unrecognised possibilities for making profit, hiding in plain sight, and entrepreneurs are similarly positioned as innately talented individuals with a knack for spotting them.

However in the narrative accounts collected for my research, opportunity spotting was only sometimes present as the impetus for starting an enterprise; personal growth, progression from freelance work, and pursuing a creative practice emerged as much stronger motivators. Where opportunities were spotted, they often came after a CCI enterprise had commenced, and this offers some examples of where Teece’s evolutionary dynamic capabilities can be seen in practice. In the example of James*, the co-founder and owner of an advertising content business, his original intent to start a business making comedy content for TV, shifted when he spotted an opportunity to make corporate content.

…a marketing person in [a government client] … she’d seen our sketch stuff and was like, you guys should pitch on this video … and you know we applied, having no idea about what the value of these things are, and what you should be doing for X dollars. You know, we just totally over blew the thing and poured a huge amount of time and energy and it was a beautiful, beautiful output and because we’ve approached it from such a non, you know, outside of the box, just cause we had no idea what, what the normal way of doing, to approach this sort of thing would be, I think it was really refreshing the approach that we had and that became our foundation client. So, we then became their video people. Like, we made so much content for [that client].

It’s kind of like, oh wow, we can do creative work and get paid for it. And you know the alternative was waiting around [for government funding] dribs and drabs of like, just, it was just such a big too hard basket, and this actually looked like a faster way that we could make, make more and cut our teeth and really learn the craft of filmmaking through our paid [work].

Eleanor, the founder of a major classical music organisation, offers a not-for-profit example. In her case, she did spot an opportunity to fill a gap in the cultural landscape and start a children’s choir, but her motivation to do so was creative, rather than financial.

…it needed to be created. There was a, you know, children’s choirs, I thought, they’re a great thing. There aren’t any in [this city]. Let’s make one! It’s not, what are going to be the barriers to doing this? I didn’t actually think like that. I just thought, it’s there to be done. Let’s do it. And that, it’s sort of been the same with all the steps along the way.

My reason for creating [it was] purely sort of, for creative satisfaction, for artistic satisfaction and for, to a lesser degree at the time, for opportunity for the kids. That it was such an incredible instrument that you know, I wanted to create this thing that people would derive incredible sort of joy from, the kids themselves and people listening. I just thought it was the best thing, so that’s why I did it. I didn’t… it wasn’t a sort of a business venture in any way. It was an artistic venture.

Eleanor’s “artistic venture” grew into a multi-million dollar not-for-profit enterprise, but her sensing of an opportunity was almost entirely driven by a personal creative ambition. So too was Sophie’s vision of creating a small press publishing house for children’s books based on traditional fables. Having pitched her initial title to various publishers, she and her partners found general support but no firm commitment to publish.

And they said, “oh, it’s beautiful. You know, we really like it” et cetera and took it to an acquisitions meeting, but it failed to go through. And then the next publisher, we took it to also said the same thing and then they said, “oh look, it’s a lovely story, beautiful illustrations, not quite commercial enough for us.” And look, you know, I, I don’t sort of get upset about those sort of things ‘cause like I have been in the business a long time and I know what it’s like in the publishing industry, but we thought, “this is stupid. This story would work. Let’s do it ourselves”.

Having spotted an opportunity for fable-based children’s books (although one as much for self-fulfillment as for commercial success), and having made a decision to proceed, Sophie and her partners turned to gathering the resources to realise their vision. In her description of what happened next, we can see examples of Teece’s “seizing” capabilities, which helped realise the project.

So, we decided, okay, we will start with our story because we didn’t want to risk anyone else’s work on it, on something that might or might not work. And I wrote another story because we decided we’ll make it two stories within the one book. […] And so, we, we put that together and [our illustrator] did wonderful illustrations. We had a lovely time doing the layout, all that sort of thing. And we registered out little press with ASIC. You know, we got our ISBNs and all that sort of thing and we started a crowdfunding campaign for the book, and we got… So, we went with a crowdfunding platform that actually allows you to keep all the money that you raised and even if you don’t reach a target because we knew we wanted to do this book. It wasn’t something that was going to fall by the wayside. So, we thought, let’s do that. And we did that, and we raised two thirds of the money for the printing and we got lots and lots of pre-orders, you know, through that because that’s a way of getting pre-orders.

And interestingly enough, some of the people who contributed to it, were people who had been at working the publishers where we had, you know, shown the book to originally, because they really loved it. And they were just so really sorry that the commercial imperatives of these big publishers meant that they couldn’t take something on that would be a bit more of a risk. So, we had a lot of support, within the writing and publishing communities and we printed 500 copies and they sold out within six weeks and so we reprinted and then we had people coming to us, you know, very well-known established authors saying look, “I’ve got, I’ve always wanted to retell these particular stories, from Scotland or from, you know, the classics, whatever. But publishers always saying, you know, it’s not commercial blah blah”. So, we actually started taking on other people.

Here we see the process of fundraising, determining methods of production and formulating a business model detailed. These “seizing” capabilities demonstrate how entrepreneurial ventures are exploited in a stable operating environment. A more volatile operating environment calls for Teece’s “transforming” capabilities. We can note these in Jim’s account of his music distribution business, one which adapted to many industry wide technological changes throughout its 20+ year history. In this excerpt, he details dealing with the systems change needed to deal with royalties from digital sales.

[the digital music emergence] was a nightmare. […] we realized we needed a new distribution system. That was a bit more bespoke. So at the time, it was, I mean, we did a reasonable amount of research. I mean, we didn’t spend two years trying to find the right system because we were under pressure. We literally were wasting time using this… MYOB wasn’t built for what we needed. I mean, we had a, we had to deal with royalties. We were doing all our royalty statements manually in Excel.

So we just were like, “we have to do, we have to do something”. And so I looked at a couple of European platforms. They were mostly built for labels who were getting distributor sales information from the UK and they would ingest those and they’d be royalty based very hard to find out. All the big UK guys have built their own distribution systems. Each one had their own and they were all different. So that’s kind of what we did.

[…] So we spent five years, six years building our own system, bit by bit. (sighs) And it was, it was hard. It was really, really hard. It became the albatross around my neck because… It was me and you know one-and-a-half computer programmers that knew what it all was. Of course, you know, they get run over by a bus and it’s like, good luck to you.

So, it was very much, you know, five years later almost at the end of this system you could go and buy something off the shelf because the technology had moved on. There was so much demand for this sort of online and platforms with sales and customers […] We’d spent all this time getting what it was that we wanted and including digital […] and you know Apple were… built [iTunes], you know had this digital platform and here’s all the stuff we need and it’s like, “what do you need? What?!”

So we had to build, we had to build, so then we had to build a digital system onto a system that we’re in the middle of building to deal with a completely new platform and deal with Apple… It wasn’t easy. But we did it!

Eventually, Jim’s business adopted systems that could deal with digital sales and found the business model changing when dealing with streaming services, rather than having complete control over a release (“with streaming we very much just an administration partner”, he noted). His ability to adapt to changing business circumstances and to work with global music streaming behemoths meant that his company continued to grow, even though the revenue streams from digital distribution varied (and continue to vary) greatly.

… the major record companies have had all the rights to all of their product with the major signings, you know, like the you know, the big signings through the 70s, 80s and 90s. They had the rights to the universe and everything, Mars, Jupiter, any type of platform that was ever going to be invented by mankind yada yada yada. Whereas independents don’t. We [were] certainly in the more of the old school sort of record company mechanics that we built our business on. We didn’t have sophisticated label deals like that.

[…] with the advent of digital and streaming and streaming in particular, the independents don’t have the what we call the jukebox in the sky, like the majors do, the majors are flush again because they have you know, the copyrights there and in, in millions and millions and millions. And, and we have our rights particularly with digital and, and more so is streaming a very case by case based.

Jim’s story outlines a company changing its business model in response to changing external forces. On a smaller scale, Susi, a visual arts class provider in regional NSW, found her business model threatened during the COVID pandemic. In my last post, I detailed how she found an opportunity within the disruption to her enterprise, to switch from in-person classes to selling art kits and delivering them directly to houses. Eventually, a government voucher scheme boosted demand for her product, but in a subsequent interview, she outlined that was in direct response to policymakers observing her entrepreneurial pivot.

[A contact] was working… on the [voucher] scheme. And in the midst of COVID, she called me and said, “just letting you know that we’ve been watching what you’re doing online with your kids and another company have been doing similar type of thing as well. And there’s a, there’s a recommendation on the Minister’s desk to open up the… vouchers to encompass materials and online learning.” And I went, great.

Yeah, so that, I was flattered because it came from what she’d been watching, because I’ve worked with her, so she’s obviously following stuff I’m doing on Facebook and Instagram, but then I also thought, oh, that’s great. But I’m also about to have a lot more competition!

Susi’s impact on government policy settings for COVID support indicates a pleasing if rare example of how Teece’s transforming capabilities can be not just a response to changing operating circumstances, but can also influence them as well.

Conclusion

The theory of dynamic capabilities, like the theory of effectuation, is an attempt to work through how entrepreneurship happens. Like effectuation, it’s also an attempt to define the processes entrepreneurs go through. But unlike effectuation, it positions these elements in terms of personal skills and attributes. Sensing, seizing and transforming opportunities are things that people do. Through Teece’s lens, there are skills that entrepreneurs demonstrate throughout the construction of their enterprises.

Are these skills innate? Can someone teach themselves – or others – these skills and thus become entrepreneurs? From the narrative accounts of CCI entrepreneurs, it seems it is a little of both. Some accounts demonstrate entrepreneurial instincts which seem to emerge naturally interviewee’s behaviour or personality. Others show clear antecedence, in which entrepreneurial habits are gradually learned from employment, from family experience, or out of necessity. We can therefore find in these accounts evidence to support the dynamic capabilities theory, even with variations springing from the particular nuances of the CCIs. Like effectuation, it seems to mirror the lived experience of these entrepreneurs, and theoretical approaches to entrepreneurship which echo what happens in practice are particularly valuable to capturing and disseminating entrepreneurial insights.

*Pseudonyms used throughout.

Teece, David J. 2009. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management: Organizing for Innovation and Growth. OUP Oxford.

Narrative inquiry favours the interviewee’s story. Considerable emphasis is placed on allowing the story being told to progress independently of direct guidance from the interviewer. Interviewers may ask a small number of open-ended questions as prompts, but the interviewee controls the direction, content and pace of their own narrative. There is insight to be gained not just from what the story contains, but how it is told, and the choices made in the telling of it.

Narrative inquiry favours the interviewee’s story. Considerable emphasis is placed on allowing the story being told to progress independently of direct guidance from the interviewer. Interviewers may ask a small number of open-ended questions as prompts, but the interviewee controls the direction, content and pace of their own narrative. There is insight to be gained not just from what the story contains, but how it is told, and the choices made in the telling of it. This sounds bad. But there was one element of this experiment which seemed to be worth persisting with: the level of engagement Mark had with his story when he saw it mapped on the canvas.

This sounds bad. But there was one element of this experiment which seemed to be worth persisting with: the level of engagement Mark had with his story when he saw it mapped on the canvas.

The other aspect of narrative research noted in my reading was the importance of engaging with an interviewee more than once. This allows an interviewee time to reflect upon the narrative they’ve produced, edit or add to the story and to reconsider what they’ve said in the initial interview. A useful technique for facilitating this reflective response is restorying, where a narrative researcher will retell the story offered by the interviewee, in order to check for veracity and to offer a deeper consideration of the narrative from the interviewee.

The other aspect of narrative research noted in my reading was the importance of engaging with an interviewee more than once. This allows an interviewee time to reflect upon the narrative they’ve produced, edit or add to the story and to reconsider what they’ve said in the initial interview. A useful technique for facilitating this reflective response is restorying, where a narrative researcher will retell the story offered by the interviewee, in order to check for veracity and to offer a deeper consideration of the narrative from the interviewee.